Time is always limited, but in these historic times, I wished to add perspective in the hopes of moving this important conversation in a productive direction.

Malcolm Gladwell continues his march toward dissension with his latest installment in the New Yorker about social media vs. social activism. Honestly, Gladwell is more than welcome to share his thoughts as it is a democratized information economy after all. I do find it alarming however, that he is wielding his influence through an equally influential medium to spin intellectual and impressionable minds in unrewarding and pointless cycles. Is he not listening to opposition or consulting existing research?

In that case Mr. Gladwell and the like, this is not for you. This is for the people who read your work and who knowingly and unknowingly contribute to the evolution of media and culture. Perhaps, we can then better understand our role within this information revolution + evolution.

In his piece in the New Yorker he asks, Does Egypt Need Twitter?

Right now there are protests in Egypt that look like they might bring down the government. There are a thousand important things that can be said about their origins and implications: as I wrote last fall in The New Yorker, “high risk” social activism requires deep roots and strong ties. But surely the least interesting fact about them is that some of the protesters may (or may not) have at one point or another employed some of the tools of the new media to communicate with one another. Please. People protested and brought down governments before Facebook was invented. They did it before the Internet came along. Barely anyone in East Germany in the nineteen-eighties had a phone—and they ended up with hundreds of thousands of people in central Leipzig and brought down a regime that we all thought would last another hundred years—and in the French Revolution the crowd in the streets spoke to one another with that strange, today largely unknown instrument known as the human voice. People with a grievance will always find ways to communicate with each other. How they choose to do it is less interesting, in the end, than why they were driven to do it in the first place.

Indeed. In the end, it is not how revolutions are organized, it is why they arise and what they change that matters to the world. Without organization however, the revolutionaries of the future will be faced with either progress or defeat. As I’ve always maintained, this current information (r)evolution that we are experiencing at varying depths globally is less about the technology and more about sociology and how it is changing our behavior and society as a result. To ignore it or discount it is absurd and irresponsible.

Good friend Mathew Ingram published a very compelling argument to Gladwell, “It’s Not Twitter or Facebook, It’s the Power of the Network.” In this thought provoking post he cites Zeynep Tufecki, a professor of sociology, who studied the revolution in Tunisia and documented how to produce outcomes through “material,” “efficient,” and “final” causes.

The source of the debate is also its weakness, relationships and technology.

Gladwell questions the alliance between deep roots and strong ties. Ingram and Tufecki argue for the the power of the networks…they are not wrong. The only side not demonstrating authority is also its strongest voice. To which I point to a prospective slipping point and say with concern, “Gladwell, your slip is showing.”

As someone who has greatly studied how movements ranging from causes to commercial can and can’t be organized through social media, I would like to move the discussion away from tools and ties.

This is perhaps where the story gets convoluted and debatable. Technology aside, it’s our ties that dictate how information travels and to what extent. But, it is also the spontaneous fusion of strong, weak and temporary ties that align around interest or emotion that propels information across vast distances with far greater velocity. This impetus is the spark, the catalyst necessary for organization, communication, and also for engendering support. You need a powerful network for this to occur…

Why?

If unity is the effect, density is the cause. But to achieve density, bonds must be formed regardless of strength or longevity quickly around a shared mission or purpose. Density cannot be achieved if the network can’t supply the necessary resources. Well, as Ingram and Tufecki point out, the potential for activation exists within Facebook and Twitter. Social networks aside, the trigger for social activism is unquestionably built-in to the internet. It’s not a switch however.

Stowe Boyd is a social philosopher, webthropologist and a dear friend. He recently spoke out against Gladwell to teach, but also remind us about the importance of density in a network effect:

Trufecki and Ingram are on to something, but they — and Gladwell — miss something very basic about the nature of Twitter and other social tools, something critical to revolution. Ideas spread more rapidly in densely connected social networks. So tools that increase the density of social connection are instrumental to the changes that spread.

At its core, Gladwell’s arguments are not about the way revolutions work, but a denial of the strength of social culture: the culture that the social web is engendering, wherever it touches us. Wherever we connect.

This is again, not about tools or ties, but the capacity for alliances to form based on connections and how information spreads across them. I would like to share with you some very interesting research from the Department of Computer Science at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. In early 2010, the research team performed a multi-part analysis of Twitter. In their conclusion they found that Twitter is a highly effective way to filter and spread relevant information. It was the rapid fusion of ties within a densely populated network to activate the density required to trigger a network effect.

The research team used the unfortunate incident of the doomed Air France flight to visualize density and distribution.

This is a demonstration of how strong, weak, and temporary ties connected for a moment to ensure that the world united around this devastating news. I’m sure we would see similar maps if we analyzed the Iran and Egypt events where Twitter played a pivotal role in unification and dissemination.

In my work, I’ve found that it takes an exceptional incident to activate density in powerful, yet expansive and distracted network. But, it is possible, and to varying degrees, it happens every day. In instances where planning and design around action and outcomes were orchestrated, the results are proven incredibly promising and replicable.

This strength of social culture is only increasing in prevalence to the point where each day, it changes our behavior online and offline incrementally. For some, the behavior is advanced while it is starting to bloom with others. This is nothing new. But, it is this culture that we are learning to embrace that over time, moves us from our “comfort zones” in the middle to the edge until finally, the edge becomes the new middle.

This is a culture shift and a culture shock. Those who embrace their role as student in these times will earn the ability to lead us toward a new era of solidarity.

UPDATE: Sharing a very interesting picture from Mediaite with a simple, yet symbolic message that reads, “Thank you Facebook.”

Connect with Brian Solis on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook

![]()

___

If you’re looking for a way to FIND answers in social media, consider Engage!: It will help…

___

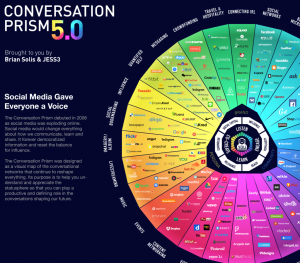

Get The Conversation Prism:

simply one of the best pieces on the information revolution, social media and the like that I’ve read up to date! Couldn’t agree more!

That means a lot Jean, thank you…

simply one of the best pieces on the information revolution, social media and the like that I’ve read up to date! Couldn’t agree more!

Brian, I have recently been reading Tony Schwartz’s wonderful “Media: The Second God”, which was written in 1981 in regards to television and radio. I can’t help but be somewhat haunted by how his words apply to what we are now experiencing with the Internet and Social Media. He says that media “makes it possible for us to take for granted what was once an exercise of faith: the miracle of speaking and listening to a disembodied voice.”

Those once voiceless voices are now being heard across the world, not in a monologue, but in multiple directions at once. I think Gladwell is truly missing something big.

Great post.

I wonder if Gladwell is hanging on so tightly because it plays right into the hands of Duncan Watts theory that challenges The Tipping Point?

Hmmmm….interesting. It’s certainly not written from experience, which is odd that someone would be so bullish without it.

Great piece Brian. I see Gladwell’s point strictly about organizing thru Twitter, etc for the protesting. Was done with the internet and after when the govt cut it off. However, he is missing many key elements of social network use as you pointed out. It is not just Gladwell (who I have mad respect for) who misses the importance of these social connections. Corporations, brands, etc. again, very well written and thanks for sharing.

Well done Brian. If you’ll indulge me, just a few days ago I wrote a brief blog post on this topic, albeit with far less analysis than you have done here (http://bit.ly/fFqrF9). But the same basic point. The continually-evolving digital behaviors speak for themselves.

To add to this discussion, the problem within these questions is perception, emotions and reason. Someone had made the comment about Facebook secret groups, where the problem is with governments taking so much time to censor and view all threats and information (See the Patriot Act), not much is missed. However, this also ties in with perception, where the one activists perspective is different than other and using the social-media network, those with minority positions are often overshadowed, downplaying the word-of-mouth amplification. On one hand, Gladwell has made a very accurate point when he describes the differences betweens the two types of activism. When it comes to emotions, social networks should be left out, for they cannot only convey emotions properly, but they also cover up true emotions, allowing one to sympathize with a view that one truly finds wrong, immoral or unjust. And finally, reason comes into play as well. Can we really, truly justify with reason our means and our actions when using social network sites to bring others to help? Trust and truth also come into question, for funding and running campaigns through networks are not only disjointed as Gladwell pointed out, but unstable as well. Just food for thought.

Thank you Brian. I’m disappointed in Gladwell. Maybe tools to communicate and share are not requisite for localized change, like East Germany or even Egypt, but they certainly enhance the potential for alliances. Thinking bigger, tools like social media are critical for true global movements that require like-minded people to gather from across the world.

Time, yes. The world has not yet seen a revolution of scale that’s possible by a network where the capacity for alignment is so extensive – especially a network that transcends borders and real world cultures and beliefs.

I agree with Gladwell. From what I read, Egypt smoothly switched to radios after Twitter and Facebook shut down, and those were hardly necessary.

The catalyst for this revolution was shared sentiments of disenfranchised educated youth…”students”. In Egypt youth unemployment reports vary from 25-40%. A study East Asian history reveals most revolutions were started that way, from the samurai to Tiananmen square, and they brought many European dictators to power.

If you’ve ever gone to a “really great party” in college, you’ll understand the massive words-from-mouth young people are capable of to disseminate information; And how they move in packs. This would be heightened in a situation of very real danger.

So if it was a revolution of the youth, and the youth use tools like Twitter and Facebook in higher proportion in the region:

“Nearly 3 million of Egypt’s 5 million Facebook subscribers are under the age of 25 years old (58%).” http://marketinghub.bayt.com/news/egypt-facebook-demographics

…then it’s not the tools that made the revolution possible, but rather the revolutionary’s use of them, which caught our attention here in the US. In effect its the people with the least involved in the situation and the longest stretch to networks who found social media as a way to feel they were participating.

Given many people who want to credit Twitter are social media evangelists, its hardly surprising. Jon Stewart did a hilarious bit on how everyone from Obama to Bush supporters wants to take credit, but people don’t send leaders to the guillotine over speeches or Tweets: They do it for bread.

Kari, it’s not a discussion about Twitter acting as a catalyst. The debate is about Gladwell’s discounting of the role online social culture (and the networks by any name) that play today and in the future of social activism.

To use your “party” example, in its most basic sense, the nature of a flashmob and the effects that networks have had around the world in their organization are also interesting to study. I’ve studied some of the network effects around SXSW when Twitter was the breakout tool for organizing people around outside events and also how Foursquare and the like facilitate density. Very interesting indeed…

But as you say “then it’s not the tools that made the revolution possible, but rather the revolutionary’s use of them.” Nailed it. Thank you for the comment.

mmm. Yes I watched Foursquare blow up over #SXSW too. Definitely interesting…I don’t know that “flash mobs” rank high on engagement though. When it comes to college parties, there’s usually a predetermined network: “That Guy” or “That Girl” who knows “everything and everyone”, and they link out in spokes of “go-to” girls and guys. Like yourself? 🙂

I think Gladwell’s point though, was to get behind a really great cause you need to trust the people, to have real life connections with them: “deep roots and strong ties.” By “revolutionary’s use of them”, I meant their preference for those tools. Its more instinctual for a 20-something to use Twitter then flyers, etc.

I think you would agree its the conversations going on off social media platforms, with someone we have history with, which most influence what we truly believe in; And what we choose to offer our support to. If you ever have a chance I would suggest reading about oxytocin, which is both the “trust” and “love” hormone. Great reminder who we are beyond the screens.

Thank you for responding, and I do hope I someday have a chance to meet you in real life. I’ve heard great things about you from many people I trust. 🙂

You probably would like to read this one: “Participatory democracy and the value of online community networks: An exploration of online and offline communities engaged in civil society and political activity” http://goo.gl/wzjBx

It’s funny because, at the core of your argument, I think you and Gladwell assert the same idea: catastrophic or significant events spark a shift in social culture, regardless of the network or medium. Essentially, the only variable that may differ in your arguments is time or the speed communication travels between people. Behaviorally, we haven’t changed from Gladwell’s French Revolution reference to the current events in Egypt. To say that we have become “more social” as a culture is also perhaps a “march towards ignorance.” Even though you say this isn’t about tools or technology, you’re still examining this issue from the lens of new media (you cite Twitter’s potential role in the unification and dissemination of current events in Egypt). Regardless, you continue to push this idea of a “social culture,” which is exactly what Gladwell is suggesting. We find ways to communicate with others about events both insignificant and important; it’s merely the velocity and reach of this dispersion of information that’s changed.

With a few exceptions, technology does not allow us to do things we could not do before the technology, it just allows us to do them faster, more efficiently and more effectively. For example, a methodology for calculating multiple regressions has been known well over 100 years. But people rarely did them before computers, because the arithmetic is time-consuming and tedious. Ordinary people rarely did these analyses before VisiCalc, 1-2-3 and Excel. Today we compute multiple regressions routinely, because the technology has made them quick and easy.

Similarly, the “new” communications tools–cell phones, Twitter, Facebook and the like–did not give us something we could not do before they arrived on the scene. We have always been able to shout at each other, post public notices, send brief messages long distances (since at least the semaphore networks of the 17th century), call people on the telephone (since the late 19th century), and organize revolutions (was Paul Revere the first tweeter? His message was 23 characters.)

These new tools just allow us to do these things easier, faster and with more effectiveness. And they have spread these capabilities widely, putting them them into the hands of fairly ordinary people.

Cell-phone penetration and broadband access throughout Egypt and Tunisia are limited, particularly outside cities. Initial demonstrations in Egypt were mostly among middle-class and educated citizens; only later–nine or more days into the crisis–did large numbers of Egypt’s poor and rural citizens join the movement, after they had had time to hear about the demonstrations, discuss the movement among themselves and travel to the nearest city. In fact, they did join, and in large numbers, but they did it without the “new” media.

Without the new communications tools, mass demonstrations would happen rarely, because they are hard to organize and motivate. With these tools, mass demonstrations are easier to organize, given a shared motivation. And educating people about their grievances, to motivate them, is also easier, more efficient and more effective. So mass demonstrations are becoming more common, just as multiple regressions have.

A retail adage says that a satisfied customer will tell three others, but a dissatisfied customer will tell eight (or 12 or 17) others. With the new media, the point remains, but the dissatisfied customer may tell 1,000 others and those 1,000 may collectively tell a million more. The point is the same, but the tools make it more efficient and effective, raising the stakes for everyone, whether participating or not.

If one cannot see the inherent power of the ever-evolving social culture that cuts across georgraphic boundaries, then that someone is missing the boat! As you aptly point out, it’s not about the technology, but what connected societies collectively can achieve by using the network effect. Just like the Net, these social tools are becoming so entrenched and pervasive in our lives that they are becoming not only our news, but also our window to news at the edges of the world that we typically don’t consider. Not to mention the real human conversation and the street level perspective that these new tools allow us all to consume. It might be a stretch for some to grok, but these tools and the freedom that they enable are very much like a “utility” to which everyone should have access. Great post and great conversation topic. Thanks Brian!

This is why I read your blog, Brian – I know at least once or twice a month you’ll hit a towering home run.

As much as I enjoy some of Gladwell’s articles and books, he does seem to pick his perspective and find everything that supports it instead of looking at both sides and coming to a conclusion. He’s had this opinion for a while. It’s an interesting opinion. Yet you can say “if people could accomplish this before without our modern technology, then it will happen anyway” for so many things in our world.

The point of technology is not always to help us do new things. New technologies improve efficiency, quality, and inevitably allows us to do more with our time. If that wasn’t true, Gladwell would be writing his pieces with fresh charcoal sticks on the stone walls of the New Yorker offices.

La Presse (the most important french speaking daily news in North America) disclosed in his daily edition of Feb 5th (unavailable online unfortunately) that a Canandian federal government founded organization, based in Montreal (Québec), has trained 120 traditionnal journalits in Egypt (that’s their expression) to social media and blogging during the last year. An external politic of Canada. Strange anyhow? I am not against but the Canadians pay for that kind of external – very external – initiative

La Presse (the most important french speaking daily news in North America) disclosed in his daily edition of Feb 5th (unavailable online unfortunately) that a Canandian federal government founded organization, based in Montreal (Québec), has trained 120 traditionnal journalits in Egypt (that’s their expression) to social media and blogging during the last year. An external politic of Canada. Strange anyhow? I am not against but the Canadians pay for that kind of external – very external – initiative

Although I’m very active in social media, I see the point Gladwell is making. He’s simply saying the revolution is bigger than social media’s role in it. I agree. The majority of social media activists seem to be saying that social media should get all the credit for enabling the revolution–as if somehow SM is bigger than the overthrow of a government. That’s like saying the Underground Railroad was bigger than the abolition of slavery. Not. This is a total confusion of means and ends. I understand this point of view, but respectfully disagree. History is on Gladwell’s side. There were lots of revolutions before social media. Now if you want to argue that social media has been an enormous tool for change and spreading the word, that’s something else. I would agree and I doubt anyone including Gladwell would disagree.

If you want a laboratory to test social science theories about “visualization of density and distribution” and such, I suggest you find a more stable and controlled environment than a street revolution. After all, proving or disproving such theories is the name of the game, and a near-war zone is pretty much tailor-made to generate bad data from which no valid conclusions may be made.

I have the utmost respect for anyone, whether using social media or not, who is directly helping the Egyptians in this struggle. But it’s time the rest of us in social media drop the self-important pretense. We are spectators in this, and there’s simply no legitimate reason for the righteous indignation.

Steven, I agree that we need to move beyond, “look how amazing we who use Twitter and Facebook are,” to the more interesting points in the conversation. Gladwell de-emphasizes the importance of loose ties and disregards much of social activism relegating it to people who simply click to join a Safe Darfur movement on Facebook. However, it is the joining of these loose ties that creates networks for information to flow quickly and in ways different than before. For some, it’s the way that this information spreads and the connections that form in the process which are as interesting and important as the content of what is being shared and its implications.

Although I’m very active in social media, I see the point Gladwell is making. He’s simply saying the revolution is bigger than social media’s role in it. I agree. The majority of social media activists seem to be saying that social media should get all the credit for enabling the revolution–as if somehow SM is bigger than the overthrow of a government. That’s like saying the Underground Railroad was bigger than the abolition of slavery. Not. This is a total confusion of means and ends. I understand this point of view, but respectfully disagree. History is on Gladwell’s side. There were lots of revolutions before social media. Now if you want to argue that social media has been an enormous tool for change and spreading the word, that’s something else. I would agree and I doubt anyone including Gladwell would disagree.

If you want a laboratory to test social science theories about “visualization of density and distribution” and such, I suggest you find a more stable and controlled environment than a street revolution. After all, proving or disproving such theories is the name of the game, and a near-war zone is pretty much tailor-made to generate bad data from which no valid conclusions may be made.

I have the utmost respect for anyone, whether using social media or not, who is directly helping the Egyptians in this struggle. But it’s time the rest of us in social media drop the self-important pretense. We are spectators in this, and there’s simply no legitimate reason for the righteous indignation.

Brian,

I read Gladwell’s piece, and others he wrote, and I read yours – I am sorry, it is me. I don’t see a dissenting point of view: you both agree that the tools are not the reason it happened, and you both say it is the social phenomenon that is people that made it happen.

He says tools are useless, or not wanted, or not necessary (my words) – ever since the origins of the world there has been Luddites (or their equivalent of the day) to any technological change. A few of your other comments said it ever so well: the tool does not bring the change, the tool accelerates the change.

This, and in every other case, proves the point.

I agree with Gladwell. All you have to do is reflect back upon how the manic SXSW pukes abandoned the Iran protesters within a few weeks. Now those hopefuls in Iran, who took to the streets after the encouragement of the weakly tied social narcissists in the USA, are spending the rest of their lives in jail.

Good job, freaky shallow twitterers.

Hey Brian,

Interesting post on a topic that really deserves more discussion.

The way I see it, we human beings have always communicated with each other to get what we need (food, shelter, love, etc.). However, as we develop new ways to communicate, I think we sometimes confuse how we communicate with why we do it. The latest technologies don’t give us new motivations for communicating, and I think this may be what Gladwell is trying to say. But I agree with you that he may be missing the bigger picture.

As you point out, social media tools not only give us the instant ability to participate in global conversations, they also allow us to network with each other for possible exponential impact. This ability to instantly build powerful networks across barriers and boundaries is potentially transformational from a cultural standpoint

If you can tell an authentic story that engages and encourages others to feel part of an experience, networks provide you with the opportunity to build and leverage immense influence more quickly than ever before. Conversely, if your story lacks authenticity, the network will quickly uncover the truth, and will either reform you, ignore you or both.

Social media democratizes communication, but networking makes it transparent. And that’s revolutionary IMHO.

Thanks again.

Jenifer @jenajean

People will always find ways to talk to each other and spread ideas be it sitting at a cafe, church pew, or on a Facebook secret group. The world evolves and so does the channels of communication. Social media is word-of-mouth amplified. The key here is people still matter and how they are using technology available to them.

It is not about what media we use to connect and communicate, to organize and effect change. Mainly what new media enable is the speed of interaction and the quick ramp-up of a groundswell.

As Brian states, a little unfathomably, “Without organization however, the revolutionaries of the future will be faced with either progress or defeat.”

CoCreatr, I can only agree. The argument outlined by Brian here is more anti-Gladwell than Gladwell’s position about social networking tools and activism. There’s also an uncanny American bias in seeing other cultures through an American lens. I have not yet seen an unbiased report about how other cultures, especially in the Middle East, use social networking tools regularly, never mind during real, on the ground social upheaval. I would guess they do not use them like Americans do, just as indigenous peoples do not use computers or digital cameras as we do in the West.

We can read the tweets pouring out of Egypt but that doesn’t in any way help us understand all the subtleties of Egyptian culture.

I don’t think anyone is arguing that Twitter helps anyone, anywhere, understand the complex entirety of a revolution. I read this as a debate regarding awareness, reach, and a social tipping point. And I think the quality of discussion on this thread speaks to value of this article.

Furthermore, I would argue that viewing other cultures through an American lens is not inherently wrong. Egyptians view things through an Egyptian lens, Germans through a German lens and so forth. Such is a product of location and education (both of which are overwhelmingly correlated to socioeconomic status). I think that’s an almost entirely separate subject than that of this article. For every individual or group to obtain an unbiased, compassionate, informed world view is certainly something to aspire to—though it is not the current US—or global—reality. We must not debate within a vacuum.

Others that have commented here are mostly correct that Twitter has not directly effected change in Egypt. 140 characters, thousands of miles, and—as Dave noted—a lack of perspective/urgency/education regarding the situation is massively difficult to overcome.

It is precisely for that reason, however, that social networking in general, and Twitter in specific, has been so critical to this massive fight. It not only served as another avenue for communication and organization within Egypt, but it also served to inform the global public in a way that historical communication methods did not and could not. Social networks spread awareness in a very different way than in-person word-of-mouth, the telephone or cable news giants. It is obviously much, much, more expedient. It is also reaching people that would never have been at the foot of the proverbial soapbox or listed on the phone tree. Where Twitter fails in complexity, it excels in bite-size education to the apathetic masses. Unlike anything else in history, modern social networks have the opportunity to peak the interest of the generally uninterested. Combatting apathy, some would argue (I’m thinking of MLK Jr, for one) is the greatest moral and political indicator of progress.

While not all those that are informed will act, all of those uniformed will certainly not.

I don’t think anyone is arguing that Twitter helps anyone, anywhere, understand the complex entirety of a revolution. I read this as a debate regarding awareness, reach, and a social tipping point. And I think the quality of discussion on this thread speaks to value of this article.

Furthermore, I would argue that viewing other cultures through an American lens is not inherently wrong. Egyptians view things through an Egyptian lens, Germans through a German lens and so forth. Such is a product of location and education (both of which are overwhelmingly correlated to socioeconomic status). I think that’s an almost entirely separate subject than that of this article. For every individual or group to obtain an unbiased, compassionate, informed world view is certainly something to aspire to—though it is not the current US—or global—reality. We must not debate within a vacuum.

Others that have commented here are mostly correct that Twitter has not directly effected change in Egypt. 140 characters, thousands of miles, and—as Dave noted—a lack of perspective/urgency/education regarding the situation is massively difficult to overcome.

It is precisely for that reason, however, that social networking in general, and Twitter in specific, has been so critical to this massive fight. It not only served as another avenue for communication and organization within Egypt, but it also served to inform the global public in a way that historical communication methods did not and could not. Social networks spread awareness in a very different way than in-person word-of-mouth, the telephone or cable news giants. It is obviously much, much, more expedient. It is also reaching people that would never have been at the foot of the proverbial soapbox or listed on the phone tree. Where Twitter fails in complexity, it excels in bite-size education to the apathetic masses. Unlike anything else in history, modern social networks have the opportunity to peak the interest of the generally uninterested. Combatting apathy, some would argue (I’m thinking of MLK Jr, for one) is the greatest moral and political indicator of progress.

While not all those that are informed will act, all of those uniformed will certainly not.

Angie, good points. Disagree wholeheartedly with the idea that it’s ok to view how other cultures use technology, through an American lens. For e.g. when we try to fix things in other cultures from a western viewpoint, this often happens http://changeobserver.designobserver.com/entry.html?entry=14038

Let me ask you this – what could a truly global iPad app look like? One that has content populated by residents of their own countries, in their own language, not translated into English, expressing themselves in their own culture.. When we look at other cultures through our own country’s lens we see only what we want to see. For e.g. old Life Magazine portraits of the Massai warrior in full uniform. He dresses for the western camera, it’s not how he actually lives his daily life. Therefore we remain uninformed.

So ok, maybe social networking tools were useful once the upheaval in Egypt was under way. How we will measure those tools’ actual effect on the outcome will be debated for ever I’m sure. Or perhaps we’ll all just forget about it like we did with the last “Twitter revolution” that wasn’t…Iran

Let me clarify. I don’t think it’s “okay” to view how other cultures use technology through an American lens. I think of cultural bias as a natural condition and, as such, overwhelmingly the status quo. That is, I kind of think it to be an individual or collective state of ignorance. It is not inherently bad to be ignorant; the negative implications are derived from remaining ignorant or becoming indifferent. To outgrow such ignorance, I believe one needs education.

So, regarding Egypt, and this original debate: I believe that social networking can help the people directly involved with a place/protest organize; it can also help those that are less intimately involved support (say by donation) a cause; both of those things can also be accomplished (though less efficiently) by traditional communication methods. My argument, in opposition to Gladwell, is that social networking has a distinct, and far-reaching, *additional* benefit.

Social chatter makes even the most remote news relatively intimate. It is information in one’s personal feed, where one is frequently engaged, and posted/recommended by one’s acquaintances. Cable news can’t so that—it may have an impact on its most devoted audience members, but that is a significantly smaller sample, and the conversation is not interactive. Even the most devoted Beck and Maddow fans must seek out their channel and time. In traditional media, the user must seek the content, and then the consumption is passive.

Social chatter is the opposite—it brings the content to the user and invites them to interact. Especially in America, and increasingly elsewhere, it is accessible. Most importantly, perhaps, is that such chatter exists in a virtual area that individuals already trust and explore for information. I think Twitter uniquely piques awareness. Awareness breeds increased interest which breeds eduction. We know that social network consumers trust the recommendations of those in their network more than they do traditional media. The same is true for other content. In the case of Egypt, it is the social connection that makes passive or active engagement more likely. Engagement is good.

Regarding social ROI: How anyone turns chatter into action is the greatest question of our industry. Influencing behavior (whether it be related to social good or consumer activity) only begins with awareness/chatter/education. It is the strength of a great campaign or movement that determines grand action and change.

If you need validation that Social Media is playing such a big role in Egypt that is a very ignorant position. It is helping immensely getting news out of Egypt. But Word of Mouth, Phones calls, Emails and SMS Text seriously make Social Media nothing but a teeny speck on the wall. I notice too many of the Social Media Talking Heads need this validation because as long as they can continue this story line it justifies them selling books, getting speaking engagements, and VCs investing in Social Networks.

But Social is such a small part of world wide communication consumption and participation. Each day even avid Social media users which is a small part of the world, still communicate much more off social. And why would someone in Egypt risk getting beaten for a Tweet when they can have a talk with someone and not be at risk?

The image at the end says: Thank you…Egypt’s Youth FACEBOOK (we are) resisting…(we are) not moving.

Ironic I think that Gladwell doesn’t recognize that tools, nay media, like Twitter get to the Tipping Point much quicker. And that’s very interesting, and challenging. East Germany had years to go before the wall came down. Regimes demonstrated greater repression. Now that’s gone. If they, or brands, don’t move quickly they will be overwhelmed in the blink of an eye.

For those who keep on hanging on to Mr. Gladwell’s words:

What some people here don’t see is that mr. Gladwell is waging a battle against social networks – putting them off as irrelevant and only usable as a waste of time.

He has shown this with his ‘slacktivism’ piece and is showing it off once again.

Though I do understand what he is going for, I think that mr Solis here is pointing out quite well where his reasoning goes awry. I actually think that mr. Gladwell has taken up a point a while ago and now has to stick by his point – that this is the ultimate reason for him writing this piece.

What I find somewhat funny is the fact that mr. Gladwell in one of his privious books states is that to be an expert on a subject you need to have put 10.000 hours of work into it. However it seems that he is writing as if he is THE expert on this subject (which in his eyes is quite impossible.)

I would also for the record like to state my opinion on this: unless this person holding up this sign is a) someone working in internetmarketin/for facebook, b) the picture is doctored or c) it is an incridble guerilla advertising campaign done by Facebook – this proves that social is a revolution.

I do not think that people realize that this is an older man (by most people in old school marketing – they would not think that this man is on FB if he were to live in the States or in Europe) in a technologically backward country. He is thanking a medium…..

I have not seen many people holding signs thanking CNN or The New Yorker for that matter…..

No, it does not trigger a revolution, and without it it is also as possible to get together a large group of protesters…. but it is also possible to create larger cities without modern technologies, but it is hard not to agree that modern technologies (car, computer, etc.) facilitize the extreme growth of cities that we are currently experiencing.

In this case, denial is a magazine in the US.

simply a great great read

Stowe Boyd’s conclusion “tools that increase the density of social connection are *instrumental* to the changes that spread.” That is a profound overreach. Nobody is pretending that SM didn’t *play a role* in the Egyptian uprising, but uprisings, rapidly spreading or not, have been going on for millenia in rural and urban communities (with their own non-digital social networks). Gladwell’s argument is merely with the overreaching self justification that SM mavens constantly bombard us with.

I think we work with a false tautology: that because Facebook and Twitter exist, and are able to broadcast the impetus and the results of a “revolution” then the revolutions in themselves must be good, and we must support those who undertake to lead them, or follow them. The problem is that people in the Western world who tap into these revolutions via these media are no more intelligent about the issue than the journalists who parachute in to report on them. What we end up with is a very overblown and exhausting reportage of an event we do not have context to understand. We, especially in the United States, end up looking at the events with our assumption that democracy always springs from such events because they are democratically inspired. That may be far from the case. It may in fact be that, like in Egypt, the collective exasperation of the economic situation led to an uprising that people were not ready to call a revolution until people who weren’t even part of the issue chose to call it such. It’s kind of a blind leading the blind, leading the blind cycle, just as is our 24/7 media cycles: people just report on the emotions and the overview, in the hopes of driving interest. But truthfully, who has time or even the interest to appreciate the granularity of every step of these so-called revolutions.

By the way, do revolutions like the alleged ones in Tunisia, Egypt, Southern Sudan, romania, wherever even bear any similarities to the way revolutions like the American departure from British rule were conducted? I ask out of ignorance, because from what I have seen, they don’t look similar at all. Which is not to say every revolutionary wears the same clothes, or walks the same. It’s just that tanks in the square and a twitter app on the phone do not a revolution make.

Let’s not forget – this is a business proposition. Solis and Gladwell are communication gurus and have invested their own professional capital on opposing sides here. If Gladwell is shown to be “incorrect” in his theses, that profits Solis’ position. If Gladwell’s POV prevails, the influence of Solis diminishes.

These men are both brilliant BUSINESSMEN, plain and simple. And in business, the desired endstate is perpetuating a profit for your business model – whether that comes in the form of articles, lectures, etc.,

Is this a passionate topic for communication professionals? Yes. But we probably need to excise the emotion from the discussion and remember it for what it is.

That’s not meant to be a cynical statement either – it’s just a fact.

Congratulations to the Egyptian people! Tonight will be remembered as the night Egypt reached the Tipping Point of their revolution!

Check out Wael Ghonim (@ghonim on Twitter). Search for him on YouTube. He’s an Egyptian who lives and works in Dubai in the Marketing department at Google. He was on leave in Egypt on #Jan25 and was blindfolded & imprisoned for 12 days for partaking in protests. He was eventually freed and you can see his interviews on YouTube.

Social Media enables people like me to connect with him and spread the word. Social Media played a critical role in building momentum for his freedom.

How do you feel about that Malcolm Gladwell?

Abbas (from Dubai)

The Facebook page for Khaled Said:

. photos of him shared through social media (“connector” + “maven” + “salesman” –> protest.)

. more than 400,000 friends

. dates, locations (and videos of) for protests

I suggest you to read “Tipping Point”, Malcom. 😉